Since isopods burst onto social media feeds with the arrival of Cubaris in the pet trade, they have been having a bit of a moment. Or really, a series of moments, with isopod clean-up crews and designer Porcellio morphs now being carried by every reptile store, and merch like isopod stickers, pins, and specialty bags now putting the terrestrial crustaceans into competition with butterflies and ants to be the most the most popular invertebrate online.

More quietly, the popularity of isopods has also brought to light their conservation status as more and more people realize that the species in their gardens often aren’t native, and that the commercialization of flashy species may not be good for their survival in the wild. Similarly, it has also revealed a staggering gap in our knowledge of isopod diversity and life history.

Image: a pin of Cubaris sp. “Rubber Ducky” available for purcahse at a recent California reptile show. Troy Guajardo.

One such gap is of North American native species. While the continent’s diversity pales in comparison to Europe and Southeast Asia, there are a number of mysterious observations on platforms like iNaturalist from the American Southwest showing species that don’t appear to have ever been recorded in the scientific literature. What work has been done is often old or of poor quality, with new species placed in waste-basket genera like Venezillo or Cubaris simply because not enough is known to say otherwise.

Recently however, there have been attempts to change that. Oonagh Degenhardt and Jeremiah Degenhardt, PhD, a father-daughter research team, recently launched a crowd-funding campaign for a project called “Undescribed and Imperiled: Describing the neglected native Venezillo of the West Coast of the United States.” Published on on the science crowd-funding website experiment.com, the project’s goal is to “…collect Venezillo specimens throughout California, Arizona, and Nevada, fully describe the morphological features of each population, and conduct phylogenetic analyses, then publish the results in a peer-reviewed journal.”

I first encountered Oonagh, AKA aniedes on iNaturalist, when she reached out to me about some Venezillo I had helped find near the California-Nevada border. Oonagh is a founding member of the American Isopod and Myriapod Group, an organization working to improve our understanding of genera like Venezillo, so I was eager to learn from her expertise with a genus I had heard rumors of but didn’t know much about.

Later, along with Jeremiah Degenhardt (AKA temminicki), we met to go looking for another species of Venezillo I had found in the San Bernardino Mountains of Southern California in 2020. When I learned about the crowd-funding launch of their project, I had to learn more.

I interviewed Oonagh about the project, her work with isopods, and what she recommends for those interested in pursuing isopodology. As a field, isopodology is a ghost in comparison to bigger names like entomology and arachnology, but through projects like this one I’m hopeful for its future. Some responses and questions have been lightly edited for clarity.

Arthroverts (AR): What’s your story with invertebrates Oonagh; what got you interested in these creatures?

Oonagh Degenhardt (OD): Ever since I was little I loved bugs and knew I wanted to work with them in some way. When I learned the word entomologist in 4th grade I knew that’s what I wanted to be. While what I ended up pursuing isn’t entomology, but rather isopodology, I think I got pretty close, and I wouldn’t have it any other way!

AR: How did you become interested in working with isopods specifically?

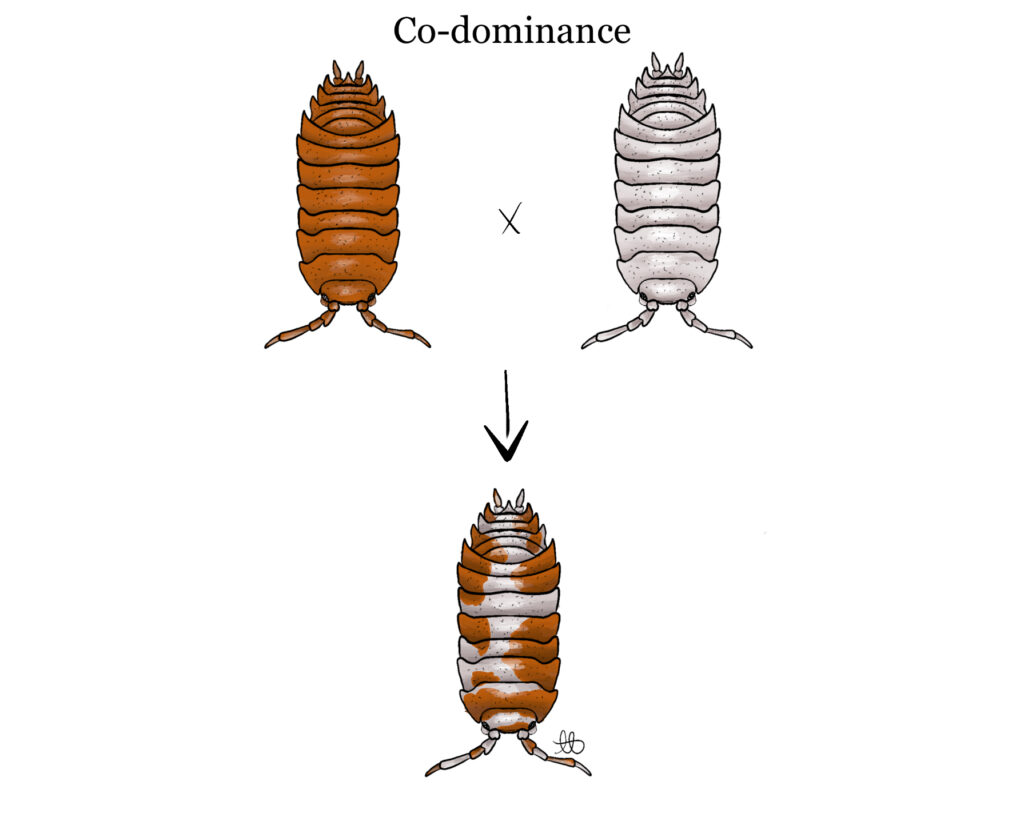

OD: Back in 2020 bioactive enclosures blew up in the pet trade and I got a few isopod colonies to put in reptile tanks. From there I became interested in their color genetics and started breeding Porcellio scaber for color. I was very interested in trying to figure out what the genetics behind their morphs were. That eventually transitioned into identifying isopods on iNaturalist (iNat) where I met the other members of the American Isopod and Myriapod Group, and I extended my knowledge on isopods further from there.

A new species of Venezillo isopod from the Mojave Desert. Oonagh Degenhardt.

AR: You’re one of the founding members of the American Isopod and Myriapod Group (AIMG). What was the process of starting that, and what is your role in it?

OD: I believe it was Nathan Jones [the leader of AIMG] who first reached out to me back in October of 2022 to ask if I wanted to help with building an educational group and website for isopods. I was super excited at the offer and agreed immediately! We started the website with 6 people and from there tried to add new pages and updates monthly for a little while. Doing the extensive research for each new page that I worked on was loads of fun and very rewarding. My current role in the group is Lead Artist, and I drew all the art that you see on the website today.

AR: As an artist, are species and taxonomic illustrations your primary work?

OD: As of right now most of my work is in the field, however, I’ve been doing a lot of taxonomic illustrations for my own work and I have done some for yet-to-be-published papers that I’m helping one of my friends with. I would love to do more illustration work for papers in the future as I find it to be quite fun to do!

An original illustration showing co-dominant genes in Porcellio isopods. Oonagh Degenhardt.

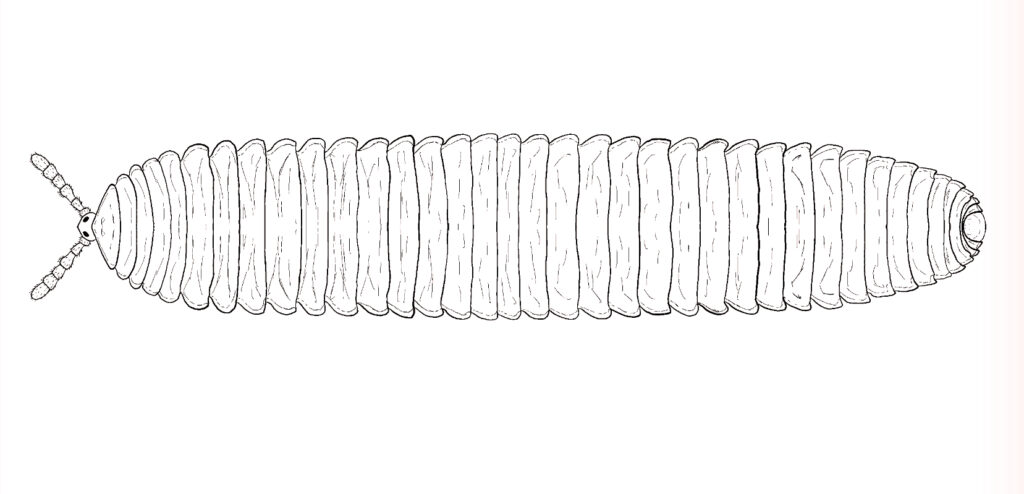

An original illustration of a polyzoniid millipede. Oonagh Degenhardt.

AR: Tell me a little bit more about your Venezillo project. Why did you choose this genus to work on?

OD: I was originally interested in the genus because of iNat observations of Venezillo microphthalmus that were posted right around where I lived. Early in 2023 I went looking for them, and eventually figured out a technique for finding them and got quite good at it! From there I looked at other iNat observations in California and became interested in the many unidentified, and very likely undescribed, species posted there. In November 2023 I managed to find one of those unidentified populations in the wild and confirmed, with the help of the other members of AIMG, that it was an undescribed species. Finding that population sparked the idea for this project in July 2024, and I’ve been fully committed to it ever since.

I looked at other iNat observations in California and became interested in the many unidentified, and very likely undescribed, species posted there.

Venezillo micropthalmus, the species that laid the groundwork for the Venezillo project. Oonagh Degenhardt.

AR: As a researcher outside of a typical institution, how are you approaching the work?

OD: I try to be as rigorous as possible to add credibility to my work, and to make up for the fact that I’m not associated with an institution. That involves doing tons of research to back up every claim and reading a lot of papers to make sure my understanding of the topic is as fleshed out as possible. I’ve also had tons of help from people with institutional knowledge. My parents are both scientists and have experience with projects similar to this, so they have helped greatly with moving this project forward. I have also reached out to researchers in my area for advice on things like storing samples and preparing slides.

AR: What’s been the most challenging aspect of this research so far? The most rewarding?

OD: The most challenging part so far has definitely been finding and collecting the southern California species because the weather conditions have to be so perfect for you to find them. There’s little to no information on the conditions that people have found them in in the past, so it’s taken a lot of attempts to figure out the correct conditions. The most rewarding part for me has to be finding a species exactly where I expected it to be after I’ve put in so much work to figure out the habitat patterns of these species and refine the technique to find them.

AR: Do you have a favorite moment or discovery from the field?

OD: My favorite moment in the field so far has been finding an undescribed species again after two years. The species is found in dune habitat and requires very specific weather for it to come up to the surface. When we found the species the first time in 2023, we only found 3 individuals, which we collected to confirm that they were undescribed. In 2024, when I decided to pursue this project, we tried to find them again. I put in tons of research to figure out when they were active, but the general lack of information and iNat observations made that difficult. We ended up making 7 separate trips to look for this species and tried to time them with different weather to figure out their activity patterns, and ultimately what ended up working was going about a week or more after the area got some rain. The day that we found them was the last day of our trip down south, and after so many unsuccessful late night searches we were pretty discouraged, but then we found them under a log at about 8pm! We put in so many hours trying to find that species again, so finally seeing them this year was a huge moment.

The most rewarding part for me has to be finding a species exactly where I expected it to be…

Venezillo arizonicus from southern Arizona. Oonagh Degenhardt.

AR: Any sneak-peeks on the results?

OD: So far we have 8 likely undescribed species in California alone, and we will probably have more as this project progresses!

AR: Isopodology has been in a limbo for a while now, with a lot of poor research making further study difficult. How do you hope to overcome that legacy through this project?

OD: My hope is that because this paper is describing so many new species in a place like California that seems so heavily researched, it will spark some interest in isopods with outside researchers and show people that there’s still a lot of work to be done even in highly populated and researched states. And even more to be done in places that haven’t seen as much study.

AR: Do you have any advice for people wanting to pursue isopodology? Anything you wish you had known before getting into it?

OD: There aren’t very many people working with isopods in academia, nor many resources on isopods outside of the pet trade, which unfortunately tends to have a lot of inaccuracies due to the lack of scientific research. Finding people who seem knowledgeable on isopods on iNat and trying to learn from them, along with a lot of your own independent research of the primary literature, is probably the best way to pursue isopodology as of right now. There’s probably several lifetimes worth of research to be done on isopods, so there’s plenty of work waiting for anyone who wishes to pursue it. It won’t be easy to get started but it’s a very rewarding field to work in.

A new Venezillo species from Northern California. Oonagh Degenhardt.

AR: Do you think citizen science, whether through platforms like iNaturalist or working groups like AIMG, could be a savior for isopodology given how few active professionals there are?

OD: For sure! I think apps like iNaturalist are helping a lot with sparking interest in isopods, and isopodology as a whole, which will hopefully lead to way more data out there for researchers to use that wasn’t there before. As an example, iNaturalist is how I originally found out about the Venezillo that I’m working on in this project!

AR: What’s a resource you’d recommend to people wanting to go deeper with isopod research? Not counting the AIMG website, ha ha.

OD: Honestly, as of right now there’s not a whole lot of websites for information on isopod research, but some good ones to check out are the British Myriapod and Isopod Group (BMIG) and the World Register of Marine Species (WORMS). I hope that in the future there’s a lot more resources for isopod research!

AR: Aside from donating (which everyone should do, go donate!), what are some of the other ways people can support your project, and isopodology research in general?

OD: Sharing helps out a ton! The more eyes on crowdfunding pages or educational websites the better! Currently isopodology isn’t very well known, even among scientists, so spreading the word is extremely helpful to researchers working in this field at the moment.

My hope is that because this paper is describing so many new species in a place like California that seems so heavily researched, it will spark some interest in isopods with outside researchers…

Another new Venezillo species from Los Angeles County, California. Oonagh Degenhardt.

AR: Any hints on what you’ll be working on next?

OD: I definitely want to continue working on the understudied native isopod species of the United States, and would love to work more with Venezillo and other genera like Brackenridgia which haven’t seen much work in a while.

AR: Do you have a favorite isopod species? A top five?

OD: As much as I absolutely love Venezillo, my favorite isopod species is probably Acanthoserolis schythei. My dream is to see one in the wild one day.

A big thank-you to Oonagh for making this interview possible. If you would like to support her research, donate to the Venezillo project (don’t delay, it’s only open for another 32 days and experiment.com uses an all-or-nothing funding model), and share it where ever you talk about invertebrates. Also consider following her on iNaturalist, as well as following the American Isopod and Myriapod Group and checking out their website. Also a thank-you to Troy Guajardo for use of his picture.

Arthroverts.org is all about seeking the lost till all is made new. For invertebrate biodiversity news and more interviews like this one, be sure to subscribe to arthroverts.org and get updated about every new story.

Arthroverts out.

Leave a Reply